The Congolese cesspool grows bigger and its terrible smell affects all of Africa

Recently, we haven't seen many news updates from the Congolese Kivu region. The Congolese army has taken a serious beating; M23 now occupies or has liberated large parts of Nord- and South Kivu. We can follow ongoing negotiations between Rwandans and Congolese officials in Washington, as well as talks between M23 and the Congolese government in Doha. An uninformed observer might think that solutions are in the making to end the regional conflict. That would be great, but the reality is far from it.

It would be naïve to believe a peaceful resolution is possible with the current cards on the table. President Tshisekedi has reached the end of his rope; he can only maintain his position or pretend to do so by stretching out negotiations. If this strategy backfires, he may resort to war again—a war he would likely lose, potentially leading to his fleeing the country and other Congolese politicians taking over. In a country where honest, capable politicians are rare, placing hope in them seems impossible.

As I have said many times over the past 30 years, covering Congo inevitably leads to cynicism. Most facts are glaringly obvious, yet few seem willing to face or resolve them. Back in the 1980s, during my first coverage of Congolese news, I was told the country had never been in such a dire state. Mobutu was still in power, but losing control. Under both Kabilas, conditions only worsened, and now many say the situation has reached a new low under Tshisekedi. How is this even possible? My analysis is based on my own findings: I have spoken to dozens of insiders in recent days. After nearly six months of inactivity, I struggled to reconnect with the realities on the ground. My frustration grew due to lack of funds, distrust, and the feeling that I might be forced to ignore certain issues or write only what others want to hear.

Despite these challenges, many followers encouraged me to pick up my pen and camera again.

First Findings...

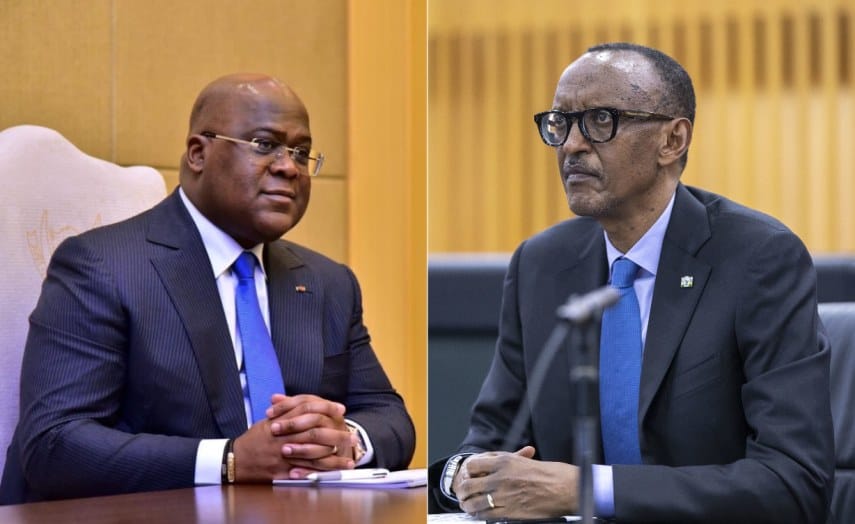

As I mentioned before, there seems to be some hope now that U.S. President Donald Trump claims to have facilitated negotiations between Rwandan and Congolese foreign ministers aimed at achieving a durable peace. A second round of talks is scheduled for June, and by July, Trump hopes to host Presidents Kagame and Tshisekedi in Washington to settle these issues once and for all. Achieving peace in Congo would be a small feather in Trump's cap—he had previously boasted that he could quickly end conflicts in Ukraine and Gaza once elected.

“What Trump is trying to do is pure window dressing,” says a well-informed Congo analyst based in Europe. “This is the result of Tshisekedi’s charm offensive in Washington, aimed at gaining American access to minerals in the DRC in exchange for support against M23. Tshisekedi likely saw an opportunity when he noticed the Americans proposing similar arguments for Ukraine. By then, he had already lost most of his other allies: South Africa ridiculed him, Burundian troops suffered defeats against M23, and the East African community learned its lessons. Europeans haven't provided the support he hoped for. Now, Rwanda and Congo are working on a 'conditional peace agreement' that would attract American business investments and mineral access. Rwandans could process raw minerals from Congo before shipping them back—on paper, an attractive deal. But lurking beneath are venomous snakes: first, Rwanda isn't the main actor in the conflict. M23 is doing most of the fighting, and it isn't a Rwandan outfit. M23 is now establishing its own administration and security forces in Kivu. Initially, they made mistakes, and trust in them waned. But they appear to now control their troops and suppress corrupt elements. They are cracking down on Wazalendo and FDLR elements infiltrating Goma and Bukavu. Tshisekedi’s first demand to the Americans was to persuade Rwanda to withdraw M23 from liberated zones and reinstate a Kinshasa-led administration—which is unlikely, Trump or not. M23 will never vacate its territories, as doing so would be seen as treason by their supporters. They fought to expel FARDC and Hutu extremists to protect Tutsi populations and allow Bagogwe refugees to return. Plus, Trump’s reputation remains highly dubious.”

“Rwanda has little to lose by cooperating with this American peace plan,” adds another observer. “But they are aware of its shaky foundation. This is Tshisekedi’s last chance to push M23 out of the region. Rwanda’s military presence and support for M23 are often misunderstood; UN expert reports are biased. European anti-Rwanda politicians, influenced by extremist Hutu lobby groups, often support and protect such narratives. The diplomatic standoff between Belgium and Kigali reflects this, and the situation isn’t likely to improve soon. Belgium has lost leverage in Washington, as the U.S. no longer considers it a reliable source of information on the Great Lakes region. If Rwanda must choose between dropping M23 and appeasing a narcissistic, unstable American president, their obvious choice is to stand firm. Rwanda has always preferred negotiations but became less flexible when it saw Tshisekedi using the FDLR as a pretext to provoke war. The U.S. may understand—though Trump might not—that Rwanda is one of Africa’s most stable countries, with a highly capable army. Without their consent, peace remains elusive. If Tshisekedi refuses to negotiate because Rwanda won’t order M23 to withdraw, he’ll find himself isolated. Trump’s belief that Rwanda and M23 will unconditionally accept Tshisekedi’s terms is wishful thinking; Kagame has learned from Zelensky how to counter external pressures in this region.”

So far, little has emerged from Doha, where M23 is meeting with Kinshasa’s delegation. The talks are secret, and the hosts are growing nervous over Kinshasa’s aggressive stance. If negotiations fail, Tshisekedi will have exhausted his last hope to maintain balance.

Congo’s situation...

The military situation in Kivu has stabilized somewhat. With FARDC largely withdrawn from “Petit Nord” and much of South Kivu, M23 is consolidating control over liberated zones and towns. “We see Wazalendo turning against FARDC in parts of South Kivu,” reports an observer on the ground. “Others surrender to M23. Sultani Makenga’s forces are reasserting themselves. Most residents in Bukavu and Goma welcome the increased security and crackdown on Wazalendo or FDLR infiltrators. Some M23 administrators are now performing reasonably well. If this trend continues, it will be difficult to reintegrate the population into the Congolese state. Economically, progress is needed: many international NGOs have pulled out, affecting local employment. Hopefully, this issue can be addressed. We also see M23 reducing excessive taxes on traders, and land registry irregularities are diminishing.”

“Burundi’s influence has waned,” says an M23 officer. “Gen. Neva is now hesitant to send Imbonerakure, FDLR, or regular troops across the border. If they do, we might pursue them into Burundi. Uvira remains a strategic target—it's the gateway to Bujumbura. There are indications that if Doha talks fail, M23 may take Uvira. Kigali has left Neva alone so far, but harboring FDLR keeps him a nuisance. In my opinion, his days—and those of his ambitious wife—are numbered.”

“Uganda plays a double game in Congo,” a Ugandan colleague tells me in Kampala. “Their goal is to control mineral- and oil-rich border areas in South Sudan and DRC. They are already heavily present militarily in the ‘Grand Nord’ of Kivu, where vast oil reserves and minerals like gold and coltan are located. To justify their presence, Uganda destabilizes these regions and keeps them poor. Many believe the ADF-Nalu terrorist group receives covert support from Kampala and the Congolese army, allowing Uganda to control local mineral trade. President Museveni assigns control to General Salim Saleh and his son Muhoozi. Similar tactics are used in South Sudan, where Saleh and Muhoozi incite conflict among ethnic groups. The M23 conflict serves as a distraction from Uganda’s broader aims—distracting the international community from their darker activities in the DRC. Global criticism of Rwanda and M23 helps Uganda hide its own dubious policies.”

Conclusion...

Before Donald Trump can parade a Congolese peace deal as a testament to his leadership, much water must flow through the Congo River. The chances of him achieving this on July 4th in Washington, with Tshisekedi and Kagame by his side, seem slim. I could be wrong; there is no military solution in the DRC, and negotiations remain the only path forward. Even a peace deal brokered by Trump could save many lives and is better than no deal at all.

Congo is a sideshow compared to Ukraine and the Arab conflicts. If Trump realizes that peace in the DRC won’t boost his global image, he might drop the matter altogether. Relying solely on Tshisekedi would be a mistake. If he wants peace in this region, he’ll have to take the Rwandan and the M23 claims into account as well. The situation remains complex and unpredictable.

To be continued...

Marc Hoogsteyns, Kivu Press Agency