The claim that Rwanda will balkanize Congo to plunder minerals is unfounded. The UN experts report reinforces this cliché

Recently, I attended a speech by a Belgian parliamentarian who strongly criticized Rwanda, alleging that the Rwandan army supports the M23 rebel group, extensively loots minerals in Congo, and aims to Balkanize the country to exploit the Kivu provinces for its own benefit. He cited the UN expert report to support his assertions. This well-meaning individual is not alone in propagating these ideas: similar narratives are also supported within the European Parliament, and many less familiar with Congo’s internal conflicts and political intricacies have begun to believe them. The mineral aspect of the current conflict in Congo has become highly significant: researchers and NGOs make thousands of dollars investigating it, and other countries play along by blaming Rwanda as the main culprit of plunder. But is this really the case? Let me lay out some facts.

Facts

To properly assess whether Rwanda is the primary looter in Congo, one must look at the entire country. There is extensive literature and numerous reports on this subject. Congo is one of the world’s most mineral-rich countries, but this has largely come at a great cost to its population: the exploitation of these minerals has primarily been carried out by foreign powers through intermediaries and shell companies that generously rewarded Congolese officials.

Belgium and the United States: Until the late 1990s, Belgium played a significant role in exploiting Katangese minerals. Historical accounts detail how King Leopold viewed Congo as his personal backyard, subjecting the local population to slavery and exploitation. As international criticism grew—especially from jealous British rivals—Leopold transferred some privileges to the Belgian colonial administration. Despite this, mineral exports to Belgium continued, processed in large smelters and diamonds were shipped to Antwerp. Notably, uranium used in the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki originated from Congo. During the Cold War, Congolese minerals were central to international political and military strategies. True independence was never fully granted: Patrice Lumumba threatened to align with the Russians, leading Western powers—particularly Belgium and the US—to assassinate him and replace him with Mobutu Sese Seko. To sustain their interests, they had to “buy off” Mobutu. Since then, such practices have persisted. The Belgian role was gradually taken over by other European countries and especially the Americans. Belgium’s continued involvement was driven by decades of expertise in the region, which today is mostly exhausted. But the colonization of Congo contributed significantly to Belgium’s’ rapid economic growth. Belgian unions also benefited, as the wealth generated often offset the social costs. Belgium’s influence helped establish a system of corruption that remains entrenched.

Over time, American interests increasingly overshadowed Belgian influence, especially as Belgium struggled to control Mobutu, who increasingly allied with China and Russia for larger bribes. Major Belgian companies like Gécamines and Union Minière were nearly drained by Mobutu and his cronies. Eventually, the US decided to replace Mobutu with Laurent Désiré Kabila, whom they believed more manageable, though this was also a mistake. The CIA, the Rwandan army, and European leaders backing the AFDL (the rebel movement that brought Kabila to power) misjudged him. Initially, Kabila clashed with Rwanda but later shifted focus toward China, much to the frustration of the Americans.

Through this US-Belgian alliance, France secured a foothold in Congo by taking control of much of the country’s oil exports via Perenco and Total. American-backed intermediaries and corrupt schemes ensured access to cheap Congolese raw materials, creating a monopoly that has now ended.

China: The Chinese have approached their quest for control over Congolese resources more pragmatically. They ask fewer questions about human rights or democratic principles—principles that are already highly questionable in Congo. By paying larger bribes to the Kabilas (and later Tshisekedi), they have largely displaced American influence. They pay their workers poorly, train Congolese troops, and hint at a desire to lift the country out of poverty through symbolic gestures. Currently, China dominates the copper and cobalt sectors, plundering the land on a massive scale and have acquired several large mines near Lubumbashi, some managed by Australian companies. They hold a monopoly on the entire copper and cobalt business in Congo. The Kabila family has played clever diplomatic games, giving the impression to the Americans that they can compete with China if they become “more compliant.” Meanwhile, Chinese trawlers are illegally fishing in Congolese waters, and Chinese traders are purchasing vast quantities of high-quality timber from illegal logging operations—just as Belgians, Indians, Lebanese, and others did before. The criminal networks behind this are extensive: some Lebanese traders, still tolerated by the Congolese government, maintain strong links with Hezbollah in Lebanon. If local officials receive their bribes, outsiders can freely make money on Congolese soil. Chinese companies operating in Congo, like their Western counterparts, are predators, often bribing officials to buy fishing licenses or logging rights, and exploiting local labor under slave-like conditions. Figures like Moise Katumbi—former governor of Katanga and now opposition figure—have also amassed wealth this way. Another notable figure is Israeli Dan Gertler, who was engaged by Kabila Jr. to secure concessions in Katanga. Despite being internationally condemned, Gertler remains at large and very wealthy.

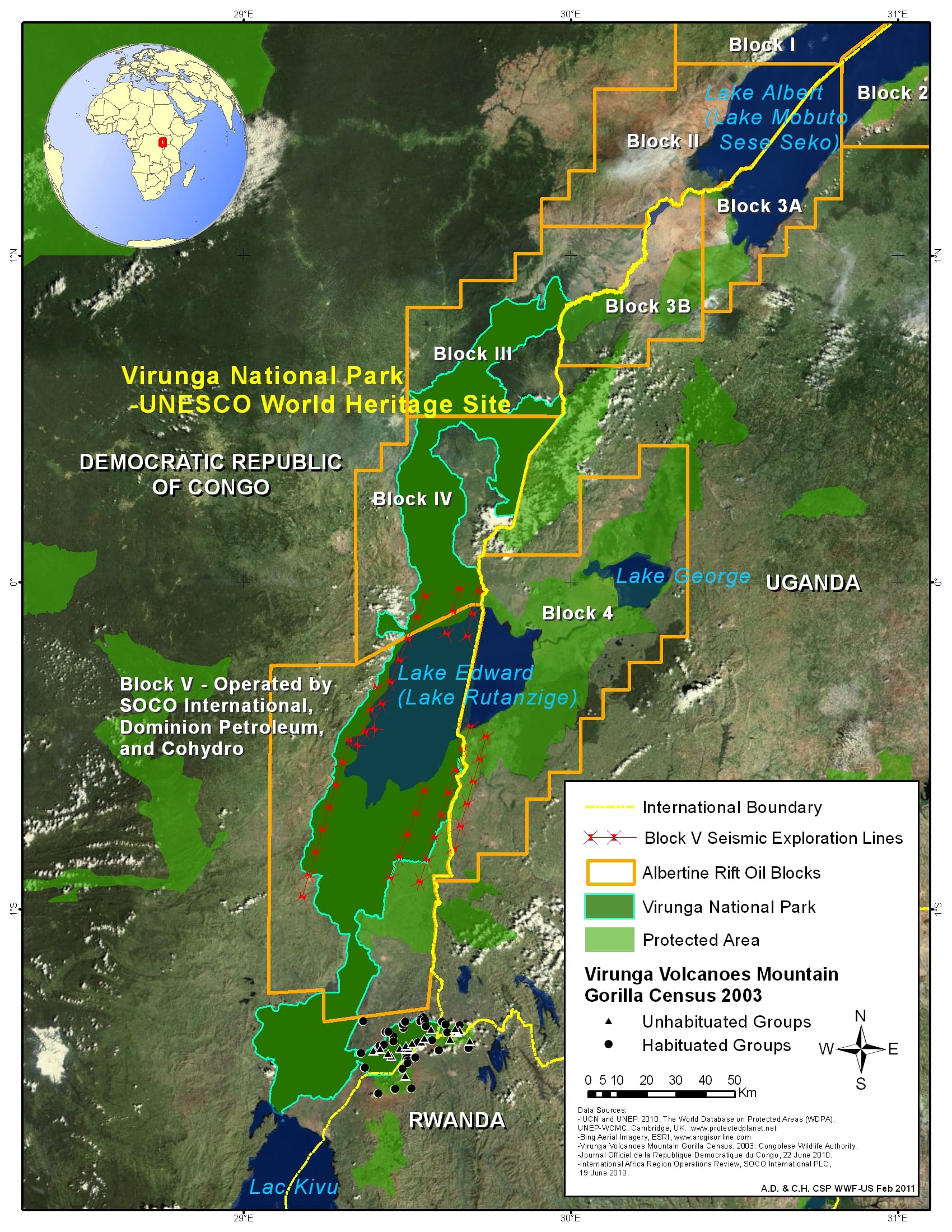

France and the UK: French and British exploitation in Congo is less extensive than that of the US or China but still significant. For example, the French company Perenco has been allowed to extract oil from Congolese waters without oversight. A decade ago, sources told me that then-President Kabila Jr. personally collected cash from Perenco every few months when visiting his large cattle farm on Mateba Island, near Boma. His armored Mercedes was transported by a heavily specially built ferry to the town of Banana, where he would indulge in luxury safaris, collecting bribe money. His younger brother Zoe also acquired and renovated luxurious hotels through similar routes. There has been little to no oversight on how companies like Perenco or the British firm Soco extract oil near Muanda, often using toxic substances that caused cancer among residents and children. Even now, this illicit activity reportedly continues, involving the same actors. Soco has operated in neighboring Congo-Brazzaville, facing widespread criticism for its environmentally destructive practices. Muanda remains one of the poorest oil towns globally. British and French companies also operate in the Kivu provinces, with Soco holding concessions near Virunga National Park. French oil giant Total extracts vast quantities of oil from Congolese waters wo now became Angolan. These criminal enterprises cross borders freely, driven by greed.

Uganda, Angola, and Burundi: The roles played by these countries are often overlooked but are crucial to understanding the ongoing violence in eastern Congo. Angola and Uganda are among the biggest African predators in this region.

It is well known that Angola controls over 40 percent of Congo’s territorial waters through various agreements with Laurent Kabila, who sought support during his war against RCD rebels and Nkunda’s CNDP. The French company Total is a major player here. To grasp Angola’s geopolitical and economic stance, we need to consider its recent history. Mobutu was initially a CIA pawn, supporting the UNITA rebels of Jonas Savimbi against the Angolan government backed by the USSR and Cuba. When Mobutu was overthrown, Savimbi faced difficulties, and Angolan President José Eduardo dos Santos pressured him, ending Savimbi’s diamond empire. Savimbi had smuggled diamonds through Kinshasa and Congo-Brazzaville to Antwerp. His fortunes declined after the Kitona operation by Rwandan forces and the RCD, which aimed to retake Kinshasa. During this operation, Rwandan troops were bombed by Angolan MiGs and Zimbabwean helicopters, forcing them to retreat. Angola was then granted access to oil and diamond concessions in parts of Congo’s territory, including near Tshikapa in Kasaï province.

Later, Joseph Kabila tried to renegotiate these arrangements but was met with resistance. Even after Dos Santos and his family were replaced by a new regime, Angola continued to maintain control over mineral-rich zones and waters, refusing to return them to Congo. In recent years, Angola has attempted to mediate between M23 and Kinshasa, but these efforts have largely failed. Their stance remains hypocritical.

Uganda’s involvement is similarly complex. Uganda holds significant interests in North Kivu, especially around Lake Albert and Lake Edward, and in areas like Bunia and Beni in Ituri. Currently, Uganda is allied with the FARDC to fight the ADF-NALU insurgents. Hundreds of Ugandan soldiers have entered Congo, but operations are slow. To understand this better, we must revisit recent history. There is a tense, often contradictory relationship between Kampala and Kigali, as Kagame and Museveni initially supported each other to oust Hutu extremists. However, rivalry and ego have since complicated matters. Some allege that Uganda supported FDLR militants by allowing them passage into Burundi, while others suggest that Museveni is jealous of Kagame’s success, as Rwanda’s development is seen as a model, while Uganda faces decline.

At times, Kampala has supported the FDLR by facilitating their movement across borders, and for years, the border between Uganda and Rwanda was closed, forcing Rwanda to rely on supplies from Tanzania. Recently, relations have improved, but Kigali remains wary of Kampala’s unpredictable motives. Museveni’s son, General Muhoozi Kainerugaba, has taken on a prominent role, often visiting Kigali and cozying up to Kagame. Meanwhile, Muhoozi also maintains close ties with the FARDC in the fight against ADF. Overall, Uganda has a larger stake in Congo’s mineral wealth than Rwanda.

Burundi is a smaller player, often described as Uganda and Angola’s “little brother” in terms of plunder. The country was on the brink of collapse due to corruption, human rights abuses, and other issues. President Neva has had to be resourceful. At one point, Burundi sent troops into Congo to fight the M23, hoping for free rein to exploit the Rubaya coltan mine and export minerals through Burundi. Previously, the mine was controlled by Edouard Mwagachuchu, a Tutsi businessman linked to FDLR, who is now in Kinshasa’s jail. The Burundese army was defeated by M23 and has since retreated to Uvira. Burundi now serves as a logistical hub for the FARDC-FDLR coalition. The future of South Kivu remains uncertain.

Interpretation

The only credible current accusation against Rwanda is that some of the Rubaya coltan may be smuggled out via Rwanda. If true, it’s a relatively minor issue compared to the vast scale of mineral theft carried out by Chinese, American, French, and British multinational corporations, and by Congolese elites like President Tshisekedi’s family (who are Belgian citizens and are publicly accused in Belgium of plundering Congo and laundering proceeds). Compared to Ugandan ambitions in Congo, the Rubaya mine is insignificant.

By examining who steals what, and where theft occurs in Congo—and who benefits—the truth becomes clearer. Rwanda is a small fish compared to the much larger European, American, and Chinese predators looting the country systematically. Yet, the latest UN report is used by these predatory interests to blame Rwanda and the M23, despite their absence from the areas where billions of dollars worth of minerals are being stolen. I asked a member of the UN expert panel why their reports don’t mention oil, cobalt, copper, or uranium theft, or the activities of China, Belgium, the US, or Angola. I was told that UN experts only have mandates to investigate conflict zones where fighting occurs. Outside these zones, they lack authority. They are professionally unconcerned with children getting cancer from toxic oil pumping in Muanda or miners being buried in poorly regulated Chinese mines in Kolwezi or Mbuyi Mayi, nor do they care about the distorted narratives used to cover up these crimes. They take pride in their work. The bias in this debate is enormous.

The Angolans and the Ugandans are also hiding behind the fact that Rwanda is getting all the blame. The Ugandans are creating chaos in neighboring countries in order to be able to stay on the spot and put their looting strategy in motion. And the Angolans are still blackmailing Kinshasa to be able to steal oil.

Finally, I was advised to take my concerns to the UN Security Council. But this is not my complaint but rather that of millions of Congolese who are used as cannon fodder or slaves and are bombarded with propaganda, much of it based on the bias that the UN experts helped to create. An important fact is that the international community continues to support President Tshisekedi, which further confirms that the conflict in eastern Congo is part of a cover-up operation designed to keep the real mafiosi out of sight.

Marc Hoogsteyns, Kivu Press Agency