The bankruptcy of the Belgian Africa policy

After the closure of the Belgian embassy in Kigali and the associated closure of the Rwandan embassy in Brussels, hundreds of Belgians remained stranded in Rwanda. Most of them had never expected that things would come to this. For simple matters such as renewing a passport, applying for a visa to Belgium, or obtaining a birth certificate, they could always rely on the embassy. However, after the Rwandan government also ended the Rwandan-Belgian cooperation and halted all Belgian development projects, many aid workers returned to Belgium. This caused confusion: for a Belgian Schengen visa, one can now only go to the Belgian embassy in Nairobi. Aid workers or diplomats whose children attended Belgian schools were forced to leave their spouses behind in Rwanda so they could enable their children to finish the school year. About 600 children are enrolled in this institution, of whom only half will remain next school year. Most Belgian teachers will also be leaving.

The biggest victims of this diplomatic dispute are therefore the Belgians and Rwandans living in Rwanda and Belgium. Several potential Belgian investors who were preparing projects in Rwanda also withdrew, fearing further measures. This small group of victims had never been particularly involved in politics; they held a rather positive view of the concept of Rwanda as developed by President Kagame. They enjoyed living and working there. But the frustration within their ranks is immense: most openly admit that the Belgian government made serious mistakes, yet they also believe that the Rwandan government reacted far too radically. Belgium’s financial aid to Rwanda was relatively limited, but those Rwandans who benefited from it now must do without.

In this paper, we aim to delve deeper into the causes of this conflict and weigh several facts against each other. I was in South Sudan when Maxime Prevot, the Belgian Minister of Foreign Affairs, made his final tour of the region. Rwanda was not on his list. I must admit that I might never have made this analysis had I not listened to our minister’s speeches in Congo and Burundi. I will try to keep it brief; the story about Belgium’s involvement in the African Great Lakes region is very complex, full of contradictions—and even serious crimes. Everyone involved in this discussion believes they are right; we are treading on very slippery ice. But, so be it!

Roots

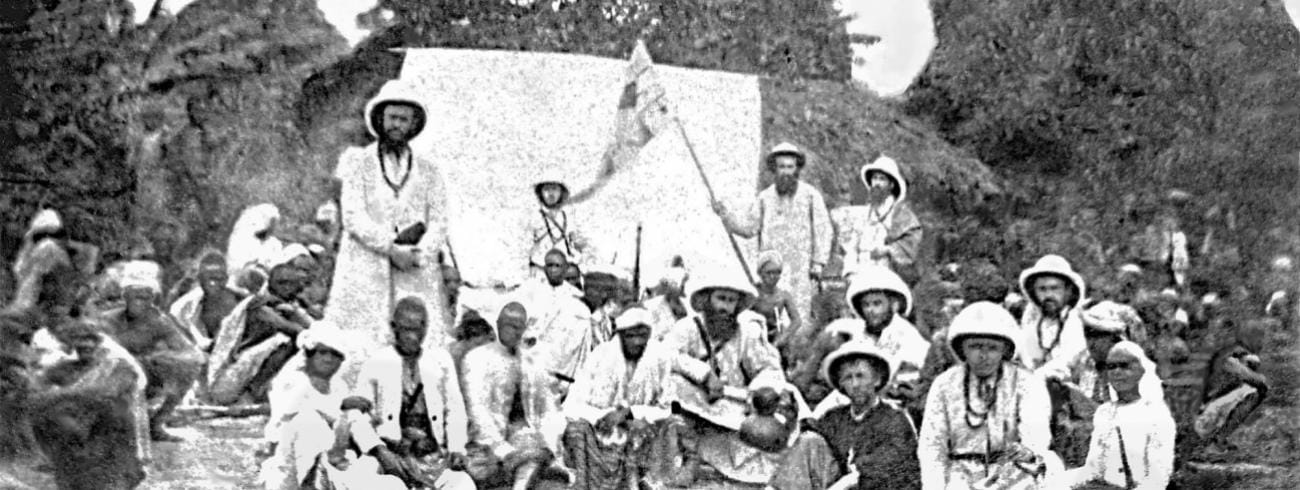

Belgium colonized Congo, Burundi, and Rwanda after the Berlin Conference of 1885. At that time, Germany still claimed rights to the so-called “Rwanda-Urundi,” but during World War I, the German army was expelled from the region, allowing Belgium to begin colonization. Colonial exploitation of Congo was already in full swing then. The colonization of Rwanda and Burundi was entrusted to Belgian missionaries, mainly White Fathers from Belgian and Dutch Limburg, a highly conservative and Catholic region. Their strategy was simple: to disrupt and manipulate the existing tribal and ethnic balance to keep everything better under control. Initially, they relied on the Tutsi minority, who led the former clans and kingdoms. But when the Tutsis began resisting, sensing that the missionaries exploited them, they could fall back on the Hutu majority, some of whom had already been trained in the mission schools to take over the Tutsi’s roles.

The 1950s and 1960s were crucial in Rwanda’s further development. The first pogroms against the Tutsi occurred. Many fled to neighboring countries; Belgium allowed Rwanda to declare independence, on the condition that a puppet regime would remain in place to defend the interests of the former colonizer. What I am writing here is well known and needs no further elaboration. The fact that Belgians had trained and manipulated the Hutu against the Tutsi behind the scenes of a heavily Catholic and paternalistic colonial regime cannot be denied. Both Rwanda and Burundi were tiny African countries, and almost everything that happened escaped international attention. But that changed in the 1980s and 1990s: the Tutsi diaspora did not remain passive. They had risen through Museveni’s new army in Uganda and began attacking the Hutu regime in Rwanda. I witnessed firsthand how, in 1990, the first attacks were carried out on Gabiro in northern Rwanda. These assaults were repelled, but by 1992, Paul Kagame’s rebel army was only thirty kilometers from the capital. I also saw how the extremist Hutu organization, the so-called ‘Interahamwe,’ murdered Tutsi huts (a type of kraal with huts where livestock was also kept). Hutu hate media incited the population to kill as many Tutsis as possible, which only spurred Paul Kagame to accelerate the liberation of his country. The Belgian mentors of the regime and the missionaries watched on. Some played a significant role in anti-Tutsi hate propaganda. A UN peacekeeping force was sent to Rwanda but was never given the mandate to stop the massacres. The Belgian government sensed the situation was escalating and handed control of the local regime over to the French, who sent the Foreign Legion to actively support the Interahamwe and the Hutu army.

Tropical nazi regime

It is a well-established fact that Belgium is 80 to 90 percent responsible for what happened before and during the genocide in Rwanda. The Belgian colonizers had also been responsible for huge atrocities in Congo. It is logical that the new rulers, Kagame’s Patriotic Front, preferred Belgium to leave after the war. In 1994, Belgium’s story in the Great Lakes region effectively came to an end. Belgium was left with a serious hangover; they had clearly failed and bore the responsibility for the lives of thousands of innocent Rwandans lost. They had actively contributed to building a tropical Nazi regime that repeatedly received the blessing of Rome, and it was difficult for them to admit this. Some parts of the Belgian political establishment did acknowledge it, but conservatives continued to hide behind the passivity of the Belgian public, which was content and fed with information from politically controlled state media. Belgium also became one of the new home bases for the extremist Hutu lobby. The children of this lobby, supported by their parents, established organizations like Jambo SPRL and networks openly supporting the extremist FDLR militia in Congo, as well as individuals like Hollywood actor Paul Rusesabagina, whose group later also murdered innocent people in Rwanda. At the same time, this Hutu lobby saw the benefit of being members of existing political parties in Belgium. Even the Belgian royal family played a role in this. I have written about this hundreds of times; all these facts are evident, but little attention seems to be paid in Belgium.

Diplomatic Bankruptcy

The main cause of Belgium’s diplomatic and political failure in this region lies in the inability of the Belgians to admit their own significant responsibility for the current chaos and to avoid actions that only deepen the confusion. Cliché arguments, overt partisanship, and one-sided positions characterize Belgium’s current Africa policy.

For example, there is a debate over the legitimacy of the M23 rebellion. Belgium has never wanted to admit that Rwanda initially played no role in it. Sultani Makenga and his group initially just wanted to be heard and sought confirmation of the agreements from 2013. The conflict in eastern Congo was then exploited by President Tshisekedi to strengthen his own power, to hide his monkey business scheme. He even began openly supporting the FDLR and arming local militias and bandit gangs. The main culprits of the current situation in eastern Congo are therefore not the Rwandans or Congolese Tutsi. Instead of adopting a neutral and conciliatory stance—one might expect this in such a charged and bloody African portfolio—Brussels continued to defend Tshisekedi’s position. The Belgian government repeatedly accused Kigali of interference in Congo, based on reports from UN experts, without critically questioning Tshisekedi’s support for the FDLR, the deployment of mercenaries, or Burundi’s interference.

Rwandan model

It is becoming increasingly clear that the Congo of the past no longer exists and cannot be restored to its original form. The M23 or the Rwandans never intended to balkanize the country, but it has come to pass because Kinshasa, supported by the international community, was never willing to negotiate with the rebels. Now, with the current situation, those zones will never relinquish control—even under pressure from the Americans. Some Belgian diplomats and Congo analysts share this view, but the Belgian government refuses to listen. Likewise, the fact that the Kagame regime is not comparable to other African countries. Kagame and his team have developed their own political model that does not align with what Europeans consider democratic. But don’t the Rwandans have the right to decide how their country is governed? Rwanda is often praised for its progress: it is safe, and in terms of human rights, it is far better than many neighboring countries such as Burundi, Uganda, Congo, and even Tanzania. The Rwandan model is even being adopted by other African nations. Yet many in Belgium continue to claim Kagame is a dictator, that he seeks to monopolize Congolese minerals, and so forth. I could give countless examples supporting this.

Rwanda was not the cause of the current problems in Congo, but it did have to act defensively once it became clear that Tshisekedi aimed for a larger conflict. The M23 has already begun preparations for the return of thousands of Bagogwe Tutsi refugees living in camps in Uganda and Rwanda. They are working on a new regional administration separate from Kinshasa’s central authority. The liberation of the areas, as demanded by Kinshasa and the UN, would never be accepted by these groups. This is their last chance to consolidate what they have achieved. Belgium, France, the United States, and the international community should realize this. Otherwise, peace in the region will never be possible.

Prevot

To be honest, I had never heard of Maxime Prevot before he became minister. But it quickly became clear that Congo and Rwanda were his pet issues. He was always quick to convince other European leaders and politicians of what he claimed was the evil nature of the Rwandan government. One recurring theme I heard him mention was that the current generation of Belgians cannot be held responsible for the mistakes of previous generations. That sounds logical, but it is also a serious mistake. An ordinary person from Liège or Limburg in his thirties cannot be held accountable for King Leopold II’s deeds or colonial errors of the past. But Prevot cannot hide behind that excuse. He is a minister of a country that bears significant responsibility for the dramatic events in Congo, Burundi, and Rwanda. Instead of fueling the fire further, he should show more forgiveness, seek negotiations, and stop continuing to support the true culprits of this conflict.

The Rwandan government is fed up with Belgian interference in this debate. In various interviews, Prevot himself indicated that, as the new Minister of Foreign Affairs, he felt it was his duty to play a prominent role in condemning Rwanda as the main instigator of all problems in Congo. The expertise on the Great Lakes region remains one of the few areas where Belgium can still exert some diplomatic influence internationally. During the Mobutu era and the regimes of the Kabilas, Belgium was a key source for the Americans and other major powers to gain insight into the situation. “Prevot is also trying to profile himself here,” said a diplomat. “The man comes from nowhere and was appointed minister in a government that has no real connection to Africa. The prime minister is a Flemish nationalist, and his foreign policy is limited to the shadow of the church tower. Prevot is a Walloon Christian Democrat, who apparently still strongly adheres to the old tradition of cooperation with Congolese leaders. The former policy of the liberals, led by Louis Michel, was quite different. They had business interests in Congo and better contacts with leaders like Kagame. Another liberal figure, Guy Verhofstadt, even officially apologized on behalf of Belgium for the mistakes made in Rwanda. But Prevot does not fit that profile. On issues like Gaza and Ukraine, Belgium tends to just follow. However, Congo remains the only domain where Belgium still has some diplomatic influence. But the Rwandans are now again too quick for them.”

A Belgian journalist colleague confirms this: “It’s not that the Belgian government doesn’t know what’s happening in the Kivus. They just refuse to translate this into a more realistic and objective diplomatic approach. And don’t forget that dozens of Congolese have now joined parties like CD&V, SP.A, N-VA, and the Walloon Christian Democrats. Some even have ties to Jambo SPRL, an extremist Hutu think tank. They don’t miss a moment to discredit Rwanda. Belgian development aid supported Rwanda with nearly 90 million euros for various projects. Kigali wanted to send that money back, effectively denying Belgium a voice. Brussels hadn’t expected that. Prevot’s reputation took a serious blow. In Rwanda, this was widely reported in the media; in Belgium, it remained silent. The average Belgian isn’t concerned about Rwanda. And that is exactly what the Rwandans don’t understand. Belgium has lost its credibility in the region with this decision—and Prevot is mainly responsible for that. Yet he seems to get away with it easily in the Belgian public.”

Burundi

I was in South Sudan when Prevot visited the region. I had to follow the details through social media. In Kampala, he was said to have asked Museveni to mediate between Belgium and Rwanda, but I doubt Kigali would take that request seriously. I read reactions from a Burundian pressure group, but my real shock came when I saw Prevot being interviewed by a local Burundian broadcaster. The inaccuracies he spouted in that interview spoke for themselves.

Belgium froze development aid to Burundi in 2015 when the country was in turmoil over elections. Dictator Pierre Nkurunziza tried to manipulate the situation. He came to power through relatively democratic elections, which many saw as proof that African countries like Burundi could function under a European style democratic model. But the European sponsors misjudged that. After a few years, the country was again plagued by corruption and repression. Freedom, including press freedom, was curtailed; opposition figures were arrested and tortured in secret prisons. Within the elite, it was no different. The struggle for power led to reprisals and massacres. Thousands of Burundians fled abroad. Nkurunziza collaborated with the Rwandan FDLR, Hutu fascists controlling part of the mineral trade in Congo and planning to destabilize Rwanda. Nkurunziza eventually disappeared from the scene and was replaced by General Neva, who began draining the country. Evidence of corruption and abuse of power mounted, and many donors—including Belgium—ceased their support in 2015.

Meanwhile, Burundi continued to descend into chaos. The Neva and Nyamitwe factions started to struggle, but international attention remained absent. The press was suppressed; Neva rented out his army to the Congolese government to fight the M23. The Inbonerakure militias—Hutu extremists trained by the FDLR—controlled much of the internal security. Alliances were forged with other Rwandan rebel groups to destabilize Rwanda. The fate of Paul Rusesabagina fits perfectly into this pattern. In exchange for his services in Congo, Neva secured guarantees over control of the coltan mines in Rubaya, but that ended in failure. The well-trained M23 rebels seized the mine, and Neva’s forces were defeated.

Gasoline war

Corruption and power struggles within Burundi’s elite led to further chaos, including a gasoline war where prices skyrocketed, the economy collapsed, and Burundi nearly ran out of fuel altogether. The situation has become even more precarious now that M23 is focusing on the Lake Tanganyika region and rumors already circulated of a possible coup. Burundi plays a destabilizing role in the region, especially as it has become a hotbed of Hutu extremism. Thousands of Burundians are living in refugee camps abroad. Rwanda and M23 recognize that peace is impossible without order in Burundi; Neva’s position has never been more vulnerable, but the international community is hesitant to intervene.

In this context, the visit and statements by Maxime Prevot should be interpreted accordingly. During his visit, the Belgian minister praised Burundian support for Tshisekedi’s regime and promised additional military and development aid. Everyone knows this aid will likely end up in the pockets of corrupt politicians. His remarks and concessions came just weeks after the diplomatic spat with Rwanda and can be seen as a retaliatory measure against Kagame. “This is just another Belgian provocation,” said a high-ranking official in Kigali. “They have completely lost their focus and are now clearly showing which side they’re on. They’re colluding with the extremist Hutu lobby, openly supporting Tshisekedi, and trying to persuade the international community to back Burundi again. That shows very little geopolitical insight.”

Uvira

Everyone expects that M23 will try again to seize Uvira and surrounding areas, and to neutralize FDLR and Wazalendo forces. This can only happen if they also deal with corrupt figures like Neva. The region risks igniting once more. “Burundi cannot and must not become the region from which the FARDC, FDLR, and Wazalendo reorganize to destabilize the Kivus,” said an M23 official. “The fact that Belgium is now openly supporting the regime only accelerates that process. The Doha negotiations are yielding nothing, and few believe Trump’s claims that a peace agreement will be signed soon. We do not want to balkanize; we are open to negotiations, but enough is enough. We have credible information that Belgium has promised to pay for the unpaid and ‘corrupt’ blocked gasoline in Tanzania, coming from Neva’s wife, to secure the elections. How stupid can a minister be to admit to this?”

Conclusion

We have the right to our opinions and to express the gut feelings of ordinary Bagogwe or Rwandans. Our findings can be compared with those of the opposing side. We base our conclusions on facts and have not often been wrong in recent years. My conclusion in this paper is that the Belgian government in recent months has mostly behaved like a toddler coloring outside the lines, which only increases chaos and misunderstanding on the ground. If Belgium wants to maintain its status as an Africa expert, it should adopt a more moderate stance. The Rwandans may overreact at times, but their attitude is understandable: they do not want to be treated as subordinates who should be grateful just for a five-franc gesture and obediently follow orders. A new wind is blowing through Africa; some West African countries have already bid farewell to the French. Rwanda demonstrates its diplomatic strength vis-à-vis Belgium, and if the Belgians are not careful, they may soon lose all influence in Congo and Burundi as well. One friend compares Prevot’s policy to Tintin’s adventure in Africa: the colonial undertone is no longer acceptable. Prevot clearly has not understood this and is still drawing beer from a forty-year-old barrel.

Not all Belgians share Prevot’s opinion, the Rwandan authorities should know this. They could adopt a slightly more flexible approach toward outsiders who have absorbed certain anti-Kigali clichés in Europe and who want to learn about the real situation in Rwanda. Only through open and honest discussion can a peaceful solution be found for Congo. But Belgium’s diplomatic failure in this region is already a fact. Future governments will face blood, sweat, and tears to repair the damage. Rwandans are a very proud people, sometimes too proud.

Marc Hoogsteyns, Kivu Press Agency