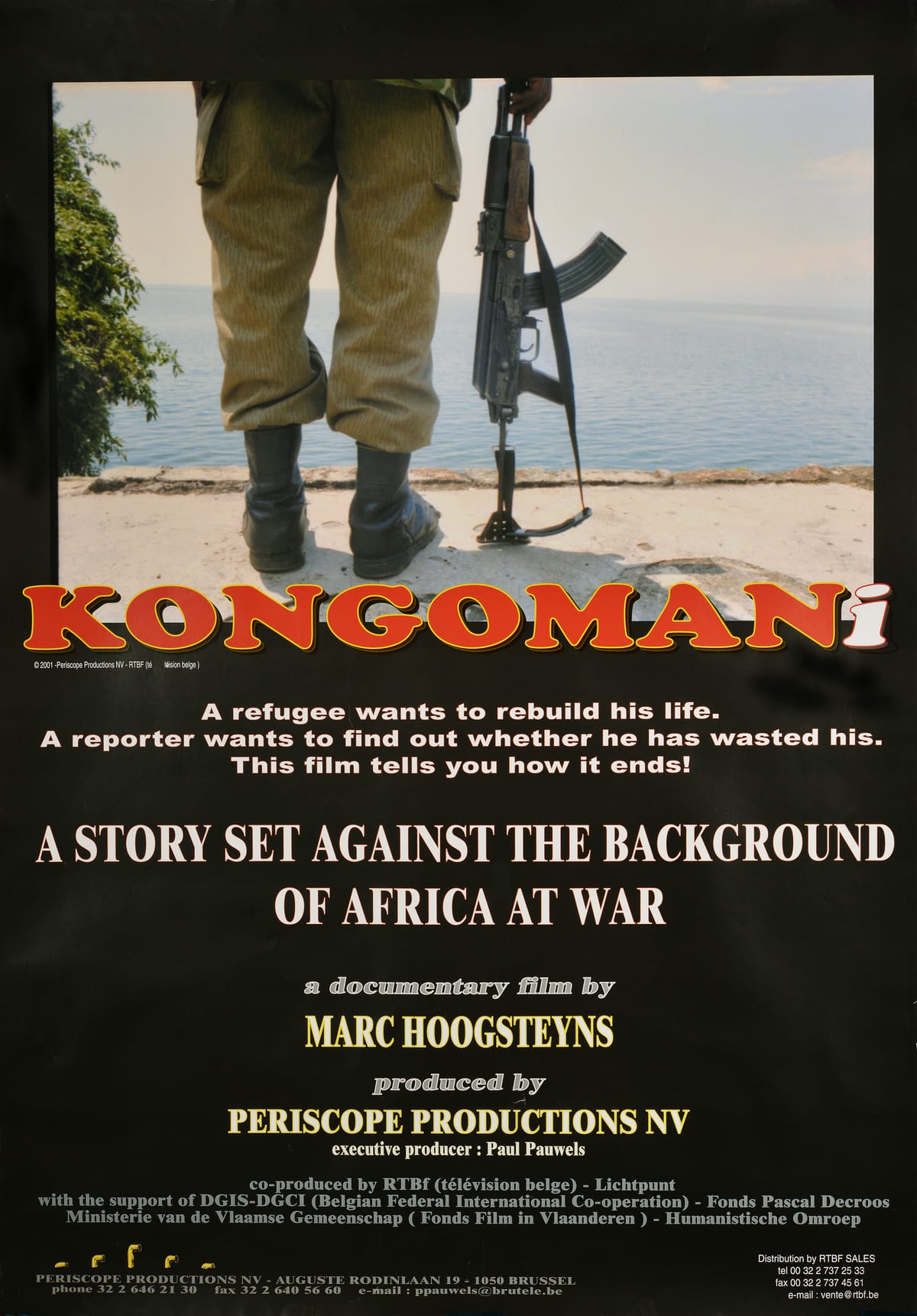

KONGOMANi revisited: lessons of the past that should not be forgotten………

Marc Hoogsteyns' story

In 2001, we finished a 45-minute documentary movie that was largely based on my own experiences and pictures covering the successive wars in the African Great Lakes Region between 1990 and the year 2000. During that period, I was a witness to the start of the rebellion in Rwanda against the Habyarimana regime, the 1994 genocide against the Tutsis itself, and the following wars in the DRC. I had lost track of the number of corpses I filmed during that period, I was getting numb to violence, and I was very lucky to be still alive after several very close calls in the field. Just after the genocide I married a woman I had met during the war in Rwanda, we had three kids, and my wife convinced me to abandon my job as a war reporter and cameraman.

We moved to Belgium, and everything seemed to be okay in the beginning. But after a while, the uneasiness in my mind started to pile up, and I started to miss my life in Africa. I was already diagnosed with PTSD before I returned to Europe, but once I arrived there, I couldn’t talk to anyone about this. In Africa, most of the people I worked with had similar experiences as I did in the past; they understood the violence of flashbacks. One of my colleagues of those days committed suicide because he could not fit in again in England, another one found refuge in heroine and alcohol, another one was shot at a roadblock in West Africa. It became clear to me that I only had one option left: return to Africa and try to make myself useful there again. Previously I already had the idea to collect the archive footage that I shot during all those years and when I heard that that many Bagogwe refugees wanted to return to their villages in the Congo I pitched an idea to a producer and friend of mine in Brussels. At that time the east of the country was controlled by the RCD “Rally for Congolese Democracy”, a rebel alliance that was supported by the Rwandan army to fight the troops of Laurent Desire Kabila who had previously fallen out with the Rwandans. This was a year before Laurent Nkunda, the famous Congolese Tutsi rebel leader, took over control in Masisi and in Rutshuru. After this documentary was broadcast, I kept a couple of copies somewhere on a shelf in our small house in Belgium. But as the war in the east of the country picked up again and as the M23 had to defend itself and started fighting back, it struck me how many similarities there were. Plunging back into the history of a conflict can contribute to a better understanding of it, and it can prevent the protagonists from making the same mistakes. Most of the characters I portrayed in KONGOMANi were killed or had to flee back to Rwanda. Others were shipped out to far away countries such as the US or Australia by international organizations such as IOM (International Organization for Migration) in the hope that this would block them from going back in the future. The return of the refugees ended up being a large failure: the project never got a green light from the international community, and they were never recognized as Congolese citizens.

Other militias such as the FDLR randomly attacked them, their own leaders made serious mistakes by overestimating their own capacity to stabilize the situation in the Kivus, the Rwandans had to withdraw their support as they were put under major pressure by the international community, etc.

We’ll come back to all that after You have watched our film!

Documentary

That’s why Adeline and I decided to post the film on YouTube. You must first look at it before we can start comparing the present with the past, talk about the mistakes that were made, and talk about a possible solution in the future. A documentary is a priori, a much more subjective tool, and in this case, it only shows what the Bagogwe themselves think about the whole situation and the way we experienced these events ourselves. This film shows what happened to the Congolese Bagogwe community before, during, and after the 1994 genocide against Tutsis in Rwanda, and it was edited in 2001, more than 20 years ago. Things that happened after that will only be described in this paper.

Here is the link to watch our film : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KpPmZJeTlTI

We hope that you found this film interesting. In a lot of respect, the situation since 2001 has not changed a lot: the Tutsi-Bagogwe community is still being targeted by several militias, and they are still fighting to defend themselves. Some of the figures in the documentary are now senior M23 and/or officers. And just like in those days, the Bagogwe are trying to rely on their own militia and a friendly, larger force to create a safe environment for the refugees to return home. This is the message they sent to their supporters in the camps to send them recruits and financial backing to fight the FDLR and the FARDC in the past and this is the argument they are using right now to attract new recruits as well. The list of similarities and contradictions is long, but we’ll try to stick to the most important ones.

Similarities and contradictions

In all those wars in which the Bagogwe were involved their principal goal was to be recognized in Congo as regular citizens and to be able to go back to their villages to reclaim their houses, their land and possibly also their livestock and their businesses.

Another, very important reason, why so many young Congolese Tutsis decided to join the respective Tutsi rebel groups in this region is the fact that it was, for them, the only way to protect their families and relatives who were still living in Masisi and in Rutshuru against the Interahamwe-RDR (‘Retour des Réfugiés ’) who later on changed the name of their outfit into FDLR (‘Democratic Front for the Liberation of Rwanda’). The FDLR hosts several smaller splinter groups of Rwandan Hutu extremists of the first and second generation, of which many of them committed crimes during the genocide in Rwanda. President Mobutu started to re-arm the FDLR when it became clear that the US, as well as several European countries, became convinced that he had served his purpose and that he should be replaced by a much less greedy leader. In those days, I filmed an attack on Iwawa Island in Lake Kivu. The Interahamwe had turned the island into a base to infiltrate Rwanda with canoes and bamboo rafts. They had entrenched themselves on the small island, beside Idjwi Island. The RDF (Rwandan army) attacked the island with speed boats and were engaged for two days in hand-to-hand combat. Those who fled were machine gunned in the water. The whole island was littered with brand new anti-personal mines, and we found other weapons that had been given to them by Mobutu & co. I used some of this footage in my documentary. Most of the pictures that I took on the island was too horrible to be used on TV. We were lucky to make it out without injuries. On the road back to Kigali my hands started shaking and I asked my colleague Chris Tomlinson (now working for a newspaper in Austin, Texas) what I had filmed there. I had a complete blackout. His answer was very short but to the point: “Pole sana, rasta! You filmed enough bad shit to keep CNN and all the mayor broadcasters in the world busy for a whole week.” If you end up in a situation like that you do not have the time to be afraid. This fear will strike you afterwards when you start asking yourself what really happened to you.

With the support of the Rwandan army a new political and military force was created: the AFDL (‘Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo-Zaire’). This group consisted in its first days of mainly of Congolese Tutsis of Banyamulenge (South Kivu) and Bagogwe (North Kivu). They had come to fight in Congo, and they had joined the AFDL for one big reason: to protect their families and to allow the other ones to return to their homes in Congo. As Mobutu’s FAZ (‘Force Armee Zairoise’) were not a match for these rebels, many of whom fought in the Rwandan army before that the Americans were able to convince the Rwandans to push and to march on Kinshasa. There they installed Laurent Desire Kabila to replace Mobutu. During the war dozens of collaborators of Mobutu changed sides and the AFDL ranks were pumped up with FAZ deserters and all kinds of militia members of other ethnic origins. Kabila stopped his collaboration with the Rwandan army several months later and many of the ex-collaborators of Mobutu remained on his side. The Rwandans left Kinshasa and set up another structure in the east of the country to defend their interests, the RCD-Goma (‘Rally for Democracy’). Many Congolese Tutsi’s felt betrayed by the fact that the AFDL had forced them to march on Kinshasa while their families in the Kivus remained unprotected. RCD-Goma was too weak.

Abacengezi

Kabila started to use the FDLR as well to fight the Tutsis, both in Congo and in Rwanda. In Rwanda, they were calling themselves ‘abacengezi’. They were using kids and old people to set up roadblocks to stop cars, after which they would run down the hill to kill everybody inside. I nearly got killed in such an ambush, just outside Ruhengeri.

Those bacengezi committed major crimes in Rwanda. They attacked a Bagogwe refugee camp in Mudende and killed hundreds of people in the most savage way. We were the first ones on the spot to film the bodies; these pictures can also be found in KONGOMANI documentary, and Boniface explains on camera what happened on that day.

Mobutu, father and son Kabila and also Felix Tshisekedi had one thing in common when it comes to their wars against Tutsi-led rebellions in the east of the country: they all started re-equipping the FDLR to fight back. As some of them even grew more corrupt than Mobutu could ever have dreamed to be, the wars in the east of the country provided enough cover for their criminal practices.

Another factor that comes back often during these different Tutsi rebellions is that once they start scoring points on the battlefield they start dreaming openly to march on Kinshasa while the people who support them behind the scenes just want their lives back in Masisi and Rutshuru and enjoy there the protection of a friendly force. Laurent Nkunda made this mistake when he was militarily very strong. But his base refused to follow him. By that time, the Tutsi community in the Kivus and in Rwanda had understood already that the AFDL adventure and the following RCD rebellions had brought them nothing useful. They had sent their sons to the frontline, and many of them were killed in faraway places such as Kitona, Matadi, Kole, Dekese, and Kindu. For a cause that was not theirs. When Nkunda started daydreaming verbally that he would march on Kinshasa, not so many Bagogwe were ready to follow him. And when the Rwandans stopped their support, the general was finished. Many staunch M23 supporters hope that Sultan Makenga and Bertrand Bisimwa will not fall into the same trap.

Another thing that can be said is the fact that the Rwandan army was always on the side of the Tutsi rebels in the DRC. And each time, the pressure of the international community was forcing them to back off their support. The main reason why Rwanda did this was to curb the growth of the Hutu extremists in the DRC to keep them out of Rwanda. Two years ago, the RDF was not involved with the M23 in Congo. And this involvement remains relatively limited until today. But now, many people in Kigali are convinced that Sultan Makenga’s army is making its last stand in the region and that this is the last opportunity they’ll get to obtain their goal. With a completely hostile Tshisekedi on power in Kinshasa, and with most of the other prominent politicians that cannot be trusted, Kigali as well will never accept to leave its border open for incursions. The bacengezi experience and the incursions of Paul Rusesebagina’s Hutu extremists in Nyungwe are still too freshly embedded in the minds of the Rwandan leadership. In the past, Kigali might have agreed to withdraw its support to the rebels, but this will probably not be the case this time.

Conclusion

My final remark when I left Kilolirwe in 2001 (we lived there with the returnees for four months in that camp) was that I was not sure at all if they would survive in that region. And this time, my intuition points in the same direction. Even though the M23 encircles Goma. The international community has never respected the rights of the Tutsi community in Rwanda and in the Congo. The UN groups of experts are accusing Rwanda of violating international law by sending troops into the DRC to back up the M23. But the same international laws were never respected when Tutsi’s were slaughtered in Rwanda in 1994. These laws also seem very far off when the Congolese army incorporates FDLR terrorists into its own ranks, funds them, and allows them to radicalize the whole Congolese Hutu population. The simple fact that all these problems could have been avoided if Kinshasa had respected the deals that were concluded with the M23 in 2013 does not even seem to be a valid argument for them any longer. When a rocket falls on an IDP camp outside Goma, the culprits are already known before the rocket, or the shell has left its canon. The M23 cannot defend itself against possible biased ballistic reports of groups or institutions that collaborate closely with the FARDC. MONUSCO has an international mandate to protect innocent civilians against aggressive and armed groups, but they seriously fail to do that. The current situation might end up in a real blood bath in and around Goma when the city implodes with all these armed groups and bandits around who will be trapped like rats in a cage. And even when Tshisekedi will be able to lure Rwanda into a bigger regional conflict, the international community will also be largely responsible for that. The M23 should have the intellectual honesty to investigate the mistakes that people like Laurent Nkunda and the leaders of the AFDL and the RCD made before them. Neglecting this might cost them dearly and might even damage their cause.

Marc Hoogsteyns

Editor: Adeline Umutoni

Kivu Press Agency