Forbidden Stories: when investigative journalism becomes a propaganda tool!

Few days ago, "Forbidden Stories", a kind of conglomerate of European investigative journalists, and in this case 17 European media outlets, launched a frontal attack on Rwanda. In our country, RTBF, Le Soir and Knack participated in the investigation. The organization published an overview of all these articles on its Facebook page. It took us about two full days to read all these articles and watch all the TV reports. We run a small video production company in Kigali and have been following the news in the African Great Lakes region since 1990. Currently, our focus is mainly on the war in eastern Congo. The debate on Rwanda has been at an impasse for years: pro-regime researchers and journalists are pitted against colleagues convinced of the opposite. There is no room for nuance and perspective. Many clichés and platitudes, widely used on social media, have also been taken up by traditional media. Threats and insinuations also abound on social media: we are often accused of being acolytes of the Kagame regime. The mere fact that we live and work here and can easily cooperate with the government is already suspicious to many colleagues in Europe. We are not blind to the regime's shortcomings, but if we react to the arguments and accusations of some colleagues abroad, we are systematically pointed at. A university professor in Europe even compared Marc Hoogsteyns to Georges Ruggiu, a Belgian who, during the 1994 genocide, was part of the editorial staff of the hate radio RTLM. Ruggiu incited the Interahamwe (Hutu extremists) to assassinate Tutsis. The professor could therefore easily be prosecuted for defamation and slander, but we simply blocked him on Twitter and Facebook. Until then, we exchanged ideas almost every week or every two weeks via WhatsApp. We have never hidden our position: we talk to everyone, we also respect freedom of expression, but we do not avoid discussions. Certainly not when the opposing party does not respect the rules and bases itself on erroneous arguments and facts. We are also very aware that the information we provide is sometimes quite one-sided because we do not always have access to all the actors in a conflict. For example, we have free access to the M23 area in Congo, but we are therefore accused of being pro-M23 by the Kinshasa regime. But it doesn't bother us that other colleagues, who are wary of the M23 cause, use our images and findings to balance their own stories and discoveries. Thus, we also believe that the journalists of Forbidden Stories have the right to write what they want, just as we have the full right to formulate our opinion about it.

We will try to react as succinctly as possible to the claims and approach of Forbidden Stories, without citing too many names, because we think the average reader cares less about that.

Investigative journalism and professional ethics, harassment

The Forbidden Stories collective claims to respect the traditional approach of professional journalism and the general ethical rules of the profession. This was absolutely not the case here.

Journalists strive to reveal new facts to better illustrate the truth. Journalistic research should also focus on the multiple versions that this truth can have, so that they can be evaluated. In this way, the reader or viewer gets a better picture of the different opinions within the described conflict. These principles were seriously violated in the Forbidden Stories articles.

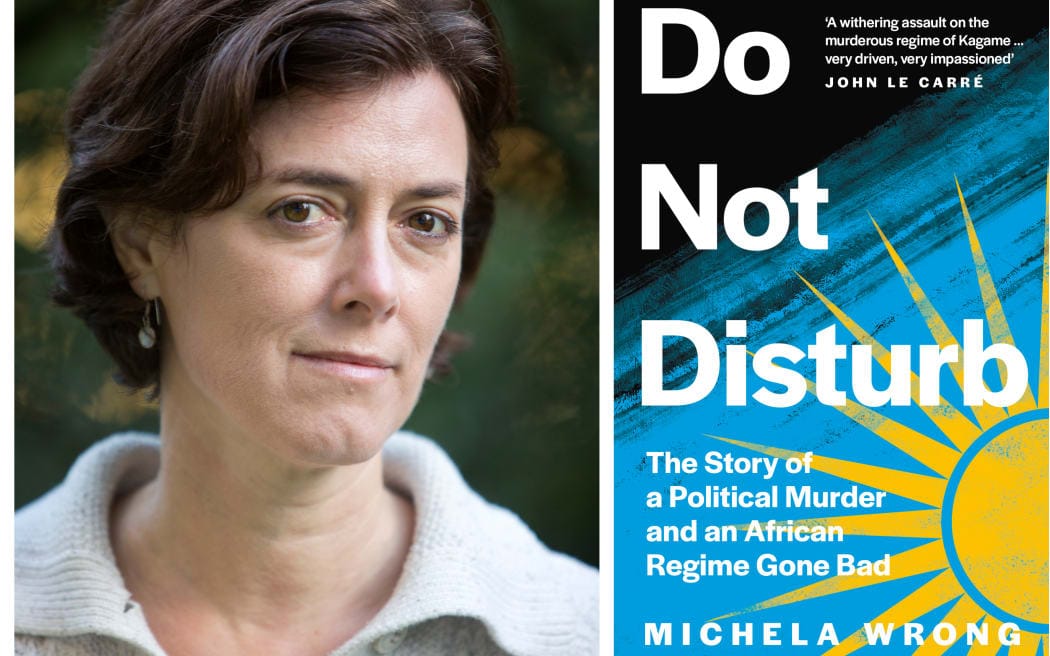

The first Knack article about the role and alleged harassment of the Rwandan embassy in Brussels against opponents is a good example. Apart from the fact that there is absolutely nothing new, the journalist relies on a number of facts that are often years old, have never been proven and have become commonplace in the rhetoric of the Rwandan opposition. Moreover, the journalist relies on five public heavyweights such as Judi Rever, Michela Wrong, Filip Reyntjens and the staff of Jambo ASBL in Brussels, of whom even the smallest child knows that they are very anti-Kigali. They do this without giving the counterpart of other people who dispute the conclusions of these people. Yet they had enough time and resources to do so. We know very well that in defense against this criticism, they will argue that they sent a whole list of questions to the spokeswoman of the Rwandan government, just before publishing their series. We learned from the office of the Rwandan government spokeswoman that during all this time, the doors of the country had remained open to come and verify these facts here and that it was not their job to do the work of these journalists. Two months ago, a few journalists from Forbidden Stories had also come to Rwanda as part of or under the guise of another mission and had even spoken to Yolande Makolo, the government spokeswoman. But they had failed to mention that they were working on the Forbidden Stories investigation and had completely missed the opportunity to ask targeted questions. The argument that the Rwandan embassy in Brussels refused to comment is also very weak: embassies generally do not react directly to open questions from the media and forward them to their superiors in their home country.

We were able to consult a copy of the list of questions that the collective sent to the OGS (Office of the Government Spokesperson) in Kigali. These questions were so detailed and often so suggestive that this service would have had to take several weeks to be able to dig up meaningful and verified facts within the various services that had been involved in these facts. So, they were not given this time, which reinforces the suspicion that Forbidden Stories already assumed (and may be also hoped) that they would not receive a response. And why would the people of the OGS (Office of the spokesperson of the government) do the jobs these journalists were supposed to do themselves? While journalists (Die Zeit and the RTBf) from the collective had traveled to Rwanda and had also missed this opportunity.

The murdered Rwandan journalist, John Ntwali

The whole Forbidden Stories story is hung on the story of a Rwandan journalist who had already indicated earlier that he feared for his life because he had published critical articles and reports on YouTube. He was also questioned by the police when he returned from Congo where he had talked to M23 deserters and FDLR members. But they didn't arrest him. We met John Ntwali several times in the field: the first time when he came to ask us in the "Bannyahe" slum why we were filming there and if we could not buy images from him. He complained bitterly about earning very little money, that his opposition contacts in the Netherlands hardly sent him any money to do this kind of reporting, and that he would rather work for real media "because this kind of odd jobs would only bring him trouble". Our night watchman and our cleaning lady also lived in this neighborhood and they told us that the journalist in question paid five dollars to anyone who dared to criticize the government.

His contacts in the Netherlands had also told him that if he did 'useful' work, it would be easier for him to escape to Europe later on. In Kinyarwanda Bannyahe means: "Where do they ease themselves?" The area was built on a swamp that makes it difficult to dig septic fosses. There was only one toilet for seven houses. The other part of the slum was also built on squatted land that was already marked for building new housing developments. The squatters therefore already knew in advance that they could only live temporarily in this neighborhood. Some of them had received relocation bonuses when they had to move by force from their previous squatted homes. And the government gave new apartments to residents outside the city. But not to those who had already received relocation bonuses before. But for the opposition, this neighborhood was proof of the alleged lack of space for the poor in the brand-new Kigali of Paul Kagame. Therefore, all the media hype around Bannyahe was largely pure demagogy. We were unable to give the journalist in question another job or buy footage from him. During the covid period, he was also part of a small group of journalists who claimed that a few Rwandan soldiers had raped some girls in Bannyahe. We also investigated this case to find that it was simply a few prostitutes who disagreed on the cost of their services, after which one of the soldiers gave them a few hard slaps. The soldiers were severely punished and expelled from the army. But there was never any question of rape.

A colleague of this man, who has since fled abroad and is now part of the Forbidden Stories collective, claims that the journalist was run over at night and that he was deliberately targeted. But that cannot be proven. We know the location of this accident very well: a small street along the main road between Sonatubes and the city center. On the other side of this road is a kind of swamp. It is almost impossible that his colleague asked a garage owner if there had been any accidents, for the simple reason that there are no garages nearby. According to our information, it is also not true that the police kept the press at a distance to cover up the trial of the drivers of the accident. Another fact is that it is very dangerous in Kigali to use motorcycle taxi’s, with which terrible road accidents occur daily. Especially at night, when there are many drunk drivers on the road. The claim that the journalist was deliberately run over to be murdered is therefore very flimsy and was taken almost verbatim from his colleague who had already managed to get asylum in Europe. It can also not be possible that the journalist was brought dead on the spot of the accident to camouflage his assassination. We won`t spent a lot of energy talking about this because it`s obvious the journalist who later fled never investigated this. In fact, the motorcycle driver is still alive and still lives in this country. We don’t think this would be the case if he transported a dead person that night to camouflage his assassination. Or he could have ended up in jail.

To maintain this shaky construction, the story of Diane Rwigara's father is added. He was a former collaborator of Kagame who fell out of favor with his boss and was also killed in a road accident. His daughter also accused the regime of being behind this "attack". The hook or the angle on which Forbidden Stories attaches this project is therefore already shaky before it can be consumed by readers or viewers.

Opposition, Michela Wrong and Judi Rever

The first Knack article completely drowns in the opposition narrative that Rwanda sends killer brigades abroad. The NRC Handelsblad goes even further. Both Knack and the NRC involve witnesses in their investigation who have been proven to have actually participated in the Interahamwe death machine responsible for the genocide in this country. One of them is cited as a "victim" who was violently punched in the face in front of "Tour & Taxis" in Brussels when Kagame gave a speech there. This brave man has more than 1000 innocent victims to his credit and was therefore placed on a kind of red list by the Dutch police. The fact that he actually committed these crimes is beyond doubt. He is still at large in the Netherlands. Knack also presents the organization Jambo ASBL as a media collective. We have questions about this; the journalist could have framed it much better for his readers by mentioning that Jambo was founded by the children of various perpetrators of the genocide who want to keep their parents' ideology alive. And by the same people who founded the terrorist FDLR.

The work and conclusions of Michela Wrong are praised by these researchers and if we understood it correctly, Wrong collaborated on this research as a consultant. One of us has worked with Michela in the past and in our opinion, she has the absolute freedom to write what she wants. But we do not agree with most of her arguments: she almost entirely based herself on the statements of Patrick Karegeya, the former head of the Rwandan intelligence service and one of the de facto architects of Rwanda's first intervention in Congo. A very intelligent guy who fell out with Kagame and then fled to South Africa where he joined General Kayumba Nyamwasa, another former pillar of the Kagame regime. Marc visited Karegeya several times in Pretoria and was able to talk to him openly for hours. On one occasion, he was even accompanied by a diplomat from the Belgian embassy. The last time he met Karegeya was in Lubumbashi, after Joseph Kabila had given him (Karegeya) a lift in his private jet to come and talk to the FDLR in Congo. Michela Wrong, who still had a good reputation in Kigali at that time, fell for Karegeya's story and failed to go and verify his theories with his former comrades-in-arms in Kigali afterwards. That is the only reproach we hav ever made to her. In itself, this is of course a rather serious professional error. Because until then, she was still highly regarded in Kigali. Her book quickly became the icing on the cake for the Rwandan opposition and several European journalists started to use her findings as the only source of truth. While some things she writes have never been proven or were even blatantly wrong. Even better: some of the accusations she made had been the work of Karegeya and Kayumba themselves, who had orchestrated the whole AFDL story in Congo. They could now whitewash themselves by distorting certain facts. But no one cared about that.

Michela Wrong is not a genocide denier, but someone who cites and believes Judi Rever as a credible source is, in our opinion, completely wrong. Rever does not hide that the genocide was provoked by the Tutsis and that Kagame & co killed as many Hutus as Tutsis. She thus joined Peter Verlinden who had in the meantime transformed the VRT into a kind of mouthpiece for the radical Hutu lobby in Belgium and always got away with it. Rever piles up the lies in her book: we have been able to check some of them ourselves. But she is also pushed by Knack into a victim role. Her life would be threatened in Brussels by Rwandan death squads. Wrong then lapses into a similar lament when she claims that the operators of ‘L'Horloge du Sud’ refused to allow her to present her book in their establishment. The truth is that these operators wanted to avoid problems in their cafe and sent everyone packing. Rever's lack of credibility is partly embellished by Wrong's better reputation and the two ladies are regularly put forward on forums of Kigali-haters such as the people of Jambo SPRL, the former Belgian ambassador to Rwanda, Johan Swinnen, etc.

The NRC Handelsblad hangs the whole Forbidden Stories story on the alleged ‘calvaire’ of the entire opposition clique surrounding Victoire Ingabire. The fact that Ingabire was at the time co-founder of the FDLR, an armed group of Hutu extremists in Congo remains hidden for the readers. She also sent money to this group. This same FDLR is today still one of the most important reasons why there is still a violent war raging in eastern Congo. At the same time, Jambo SPRL was also created. In these articles, Ingabire is also described as a victim. Her mother is also mentioned in genocide files in Rwanda, but for the journalists, this is simply proof that Kigali wanted to present her character in a bad and suspicious light. Ingabire worked closely with Charles Ndereyehe, the man who was slapped in the face on the sidewalk of Tour & Taxis in Brussels and who had hundreds of people murdered here in Rwanda. Ndereyehe is a mass murderer who has always managed to stay out of the rain. That he is presented by the NRC Handelsblad as a victim of harassment is a direct insult to the memory of the victims of his crimes.

South Africa

The second Knack article detailing the current diplomatic standoff between Rwanda and Belgium is a bit better than the first because most of the facts mentioned in it are probably quite new to the Belgian public. Knack probably bases itself here almost entirely on the findings of their RTBF colleagues who traveled to South Africa to check who had killed Hassan Ngeze's son, Thomas. And later also his Belgian friend-lawyer (Pieter-Jan Saelens) who lived in South Africa and whom the young man's family had asked to check what had happened to their son. Saelens' charred body was found by the South African police.

Hassan Ngeze is the Rwandan Hutu extremist who, before the 1994 genocide, wrote the ten commandments of the Hutus, an extremist pamphlet, a mini-bible for Hutu killers. His son Thomas had come to see us in Kigali before leaving for South Africa and he told us that he wanted to see with his own eyes how the country was evolving. Nothing of nobody prevented him from visiting people and traveling. He said that he initially believed the story that his father and his friends were innocent, but that he wanted to make sure of the truth himself. He also said that in circles of other children of genocide criminals, reactions were very negative when he told them that he would go to Rwanda. The Rwandan services were absolutely not after this young man. However, no one knows exactly what happened to him in South Africa. And no one knows how Pieter-Jan Saelens met his end. But creating the perception that the Rwandan services were behind it anyway is a dishonest journalistic act. Especially when you know that by filing a complaint with the Belgian police for crimes against Belgians in South Africa, this can also have diplomatic consequences. The RTBf journalist who shot this feature and who went to South-Africa to investigate these cases came back empty handed. The father of the Belgian lawyer who was also interviewed told her that he didn’t think that the death of his son had anything to do with the killing of Thomas Ngeze. So, we asked her (the journalist) why the argument of the two killings where copied and described by her colleagues of Forbidden stories as ‘suspicious’. She had no case at all to describe them as such. We also asked her how on earth it could be possible that convicted genocide criminals or people who collaborated openly with the FDLR – officially this group is a terrorist organization just like Al Qaida - could be described as victims of harassment and/or political discrimination. Her answer flabbergasted me; she explained in detail that each medium that participated was responsible for what they published in their own newspapers or magazines. This does not make sense to us: they all took cover under the big Forbidden stories umbrella, labeled it as investigative journalism and they hooked up the whole project on the story of a poor misguided journalist who got ran over by a car at four o’clock in the morning without being able to come up with evidence that Rwandan officials killed him. To beef up their stories they dug up old stories that were never proven as well and they covered all that under the whole Hutu extremist narrative. They copied and used each other’s stories but when somebody confronts them with the real facts they start pointing fingers at each other. Before joining this crew, they first had to sign a paper that blocked them from telling outsiders what exactly happened in the group and how this project was conceived. An internal and very well protected data bank was set up to exchange info amongst each other.

Rusesabagina

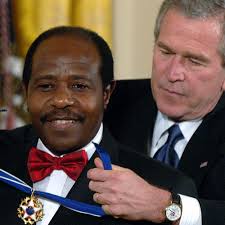

Knack also mentions Paul Rusesabagina, the former director of Hotel Diplomat in Kiyovu and the interim manager of the Mille Collines Hotel during the genocide. He was parachuted into a hero role after the Hollywood movie "Hotel Rwanda" was released. But the script of this film did not correspond at all to reality and even the commander of the UN troops who were also present at the time later stated that it was the UN troops who ensured that a number of refugees in the hotel survived the debacle of the genocide. The "golden boy" Rusesabagina was convinced by the opposition to lead a new rebel army composed of Kayumba Nyamwasa's RNC (Rwandan National Congress), a faction of the FDLR and Burundian Hutu extremists. On YouTube, he openly stated that armed resistance was the only way to bring down the regime in Kigali. His little rebel army was quickly routed by the Rwandan army but had still managed to kill several innocent civilians. Rusesabagina was trapped by the Rwandan security service NISS and was imprisoned. But the Americans continued to put pressure to have him released and currently the Hollywood hero is free again. However, the Americans have never denied that he was responsible for the deaths of nearly twenty innocent victims. His daughter, Carine, quickly became a new media star during the campaign to get him released. It was at that precise moment that Knack published an article stating that the phone of Carine Kanimba and a few other anti-Kigali figures were infected with the Israeli Pegasus virus.

All the fuss about Pegasus is, in our opinion, totally exaggerated; in an era where anyone's phone can be hacked randomly or involuntarily by programs like Pegasus (or other programs), this seems almost trivial. In reality, all foreign intelligence services engage in this. To give you a small example, we know for example from a very good source that the phones of most political and military actors in the Congolese Kivus are monitored by at least four or five foreign services. The Rwandan opposition in Brussels directs the radical FDLR in Congo and thus also bombards itself as a potential victim of piracy. The FDLR are officially known as a terrorist organization and their interactions and their history with Jambo SPRL are common knowledge. The Rwandan NISS therefore keeps a close eye on them. That they infiltrated both Jambo and the FDLR is beyond doubt. They don't even need phones to know what's going on. And they were also warned in advance that this media attack was going to take place. Hacking has become the most normal thing in the world and a fact that no one can ignore anymore. But the Pegasus story was again whipped cream on the cake for the Rwandan opposition. Yet Knack and thus also the other media that collaborated on this Forbidden Stories project manage again not to frame it properly. They simply surf on the innate paranoia of this clique of hypochondriacs who excessively demonize their opponents to get more play in the media.

The only sensible reaction in the Knack article came from the boss of the Belgian military intelligence service who rightly insinuated that the Rwandan opposition in Belgium likes to immerse itself too much in this kind of paranoia. He also admits that there were problems in the past in the Rwandan diaspora community but that this situation has improved considerably.

Shock effect

We wish no one any harm and several decades of reporting news from the African Great Lakes region have made us cynical enough to expect anything. But this project really caught our attention, especially because so many media participated in it. The shock effect of this operation cannot therefore be underestimated because the damage caused is therefore quite significant. While Rwanda is currently doing a lot to improve the standard of living of its population, help other African countries with all kinds of unilateral and lateral deals, tourism is becoming very important here, etc. That the press here is not as free as in most European countries is also a fact, especially to prevent the hate mill of the past from being reactivated. Criticism is allowed but in a constructive way and without hitting below the belt. The same hate mill is running at full speed today in Congo and Burundi and is also fueled by a number of sources that Forbidden Stories cites as victims. Rwanda has also developed its own political system and calls itself a kind of "consensual democracy", one in which everyone can participate on the sole condition that they will not drag the country back into the abyss. People like Ingabire and organizations like Jambo SPRL fall into this last category.

The portrait of Rwanda painted in these newspapers does not match reality. Some things are going wrong in this country and the regime also made serious mistakes in the past. But they have learned a lot from these mistakes; they have become much more communicative and now they think twice or three times before making a decision. The question we are now asking ourselves is why the editors-in-chief of all these newspapers were able to let this unfounded project pass. It therefore appears that Forbidden Stories allowed itself to be guided in its analyses by facts that had been known for much longer and that had already been disputed several times by the accused concerned.

Nothing new and nothing proven

There are no new facts in this investigation. Another finding is that they proceeded in a very one-sided manner and wrapped themselves in the narrative of the Rwandan opposition. It also immediately became clear that they were very poorly informed about the general context and the background of this whole story. What also immediately became clear is that the experienced Rwanda and Congo experts in these editorial offices were deliberately excluded from this investigation. We know this from a very good source from a few fellow journalists in these editorial offices. Forbidden Stories also failed to investigate the place where all these so-called "crimes" were committed, while they had the means and the time and, in a few cases, also had journalists on the spot who could have done this. To base oneself on the investigation of a few Rwandan journalists who initially allowed themselves to be financed by the opposition in the Netherlands is very weak. The leader of that opposition, the daughter of a genocide convict, admits in the NRC Handelsblad that they pushed or tried to convince Ntwali - the journalist who died in that traffic accident - to continue making reports on YouTube and the journalist told us himself that they only paid him peanuts (so very little money!) for this. We are not writing this for fun and we continue to respect our colleague, but it seems that the man was manipulated and that he was to some extent a victim of his own gullibility. Ntwali was also interviewed by Al Jazeera and thus gained more notoriety. This made his case more useful for Forbidden Stories who used him after his death to portray Rwanda as a dictatorial snake pit.

Just like Michela Wrong, this collective of journalists could have done their own research on the ground. We are convinced that the Rwandan authorities would not have hindered them much in this. The whole affair reminds us of a Zembla reporting team (Dutch tv) that came last year to make a report on how Rwanda had used the subsidies from the Netherlands to build new prisons. The journalist they had sent was so poorly informed about the Rwandan political and historical context and was already so full of the prejudices that had been instilled in him in the Netherlands that he walked around in Kigali like a chicken without a head (even without his eyes he kept on seeing ghosts). This man also called himself an investigative journalist and he based his story on the same sources as the Forbidden Stories journalists. We arranged a few appointments for Zembla and if the cameraman of this crew had not been a former colleague and friend of ours, we would have dropped them on the spot like a stone.

This project is for us a real slap in the face of the basic principles of investigative journalism. We wonder if most of the journalists involved realize this. They brought nothing new and hung their entire theory on floating facts that they could not prove. Or did they just want to add this project to their CV to get even better paid jobs in the future? We have already let the Knack journalist (whom we know quite well) know what we think of his writings and he replied that he doesn't care and that he is free to publish what he wants. That is true, but we hope that this reaction will still make him think. We can't do more than that.

We have no illusions that this text will change much of this. We are too small and powerless for that. We don't have big editorial offices behind us and we realize very well that our criticism will push us even further into the pro-Kigali adept’s box. But that can't bother us anymore either. We try above all to remain honest. And we are therefore also not financed by the Rwandan government to produce propaganda. We have nothing to hide and are open to colleagues who want to go on the road with us in the region. We also focused on what was published in Belgium and the Netherlands. Other Forbidden Stories journalists even based themselves on the statements of media criminals like Charles Onana who is on the payroll of Patrick Muyaya, the Congolese minister of information, and whose writings are even rejected as pure fiction by fervent opponents of Kigali. Our professional middle finger will always be ready to continue criticizing this kind of hoax.

NB: Our colleagues from Jeune Afrique and Le Point in France have also already reacted in detail to the offensive of Forbidden Stories and/or Rwanda Classified. https://www.jeuneafrique.com/1573888/politique/rwanda-classified-une-enquete-a-charge/

We are therefore not the only ones reacting.

Adeline Umutoni & Marc Hoogsteyns, Kivu Press Agency – Kigali - Rwanda