Denmark politician’s shielding of a genocide suspect gives support to impunity . The case of Wenceslas Twagirayezu

Busasamana, a little village in Rwanda, not far from the Rubavu district, on the border with the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), is the hometown of Wenceslas Twagirayezu, a man in his 50s who has lived in Denmark for 25 years and was wanted in Rwanda for crimes allegedly committed during the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi.

The Rwandan prosecution alleges that Twagirayezu commanded attacks on Busasamana Catholic Parish, where 1,000 of the 3,000 Tutsi who had sought refuge there were murdered, at the then Mudende University and, according to witnesses, he was among the ‘ring leaders’ who organized roadblocks in Busasamana, and other areas.

Wenceslas Twagirayezu was arrested and extradited, in December 2018, to face trial in Rwanda, following an international arrest warrant issued by Rwandan Prosecution and subsequent investigations by Danish Prosecution authorities.

Danish politician’s support

In 2003 moved to Denmark as a refugee where he met and befriended Rasmus Hylleberg, a Danish politician, at a local Baptist Church where Twagirayezu had secured employment.

Hylleberg became Twagirayezu’s protector in the latter’s efforts to evade justice.

In 2017, when Danish police arrested Twagirayezu, Hylleberg travelled to Rwanda to ‘investigate’ the case himself, becoming the face of Twagirayezu’s defense. Together with a Congolese pastor, he drafted a petition to Congolese members of the Baptist Church, to assert Twagirayezu’s innocence.

Hylleberg handed the results of his ‘investigations’ over to the Danish police; the latter recognized the charade and refused to consider those ‘findings.’ Twagirayezu was extradited, albeit with two conditions: one, in the event he is acquitted of the crimes he would return to Denmark; two, if found guilty he would be granted the possibility of carrying out his sentence in a Danish prison.

Hylleberg isn’t just supporting his friend, however. He has a personal stake in the outcome of the case: a guilty conviction for Twagirayezu is likely to hurt Hylleberg’s election for parliament in Denmark. He would be associated with a genocide convict and that is not good optics for a political campaign.

Media campaign

A media crew from DRTV, a Danish television channel, flew to Rwanda to cover Twagirayezu’s trial in 2022. They were allowed to film live court proceedings, and they visited locations, that had been mentioned during the hearing as crime scenes, to interview witnesses for a documentary they released in April 2023.

Rasmus Hylleberg and Héritier Mugisha (son of Twagirayezu) attended the whole hearing session. Both parties were closely interacting.

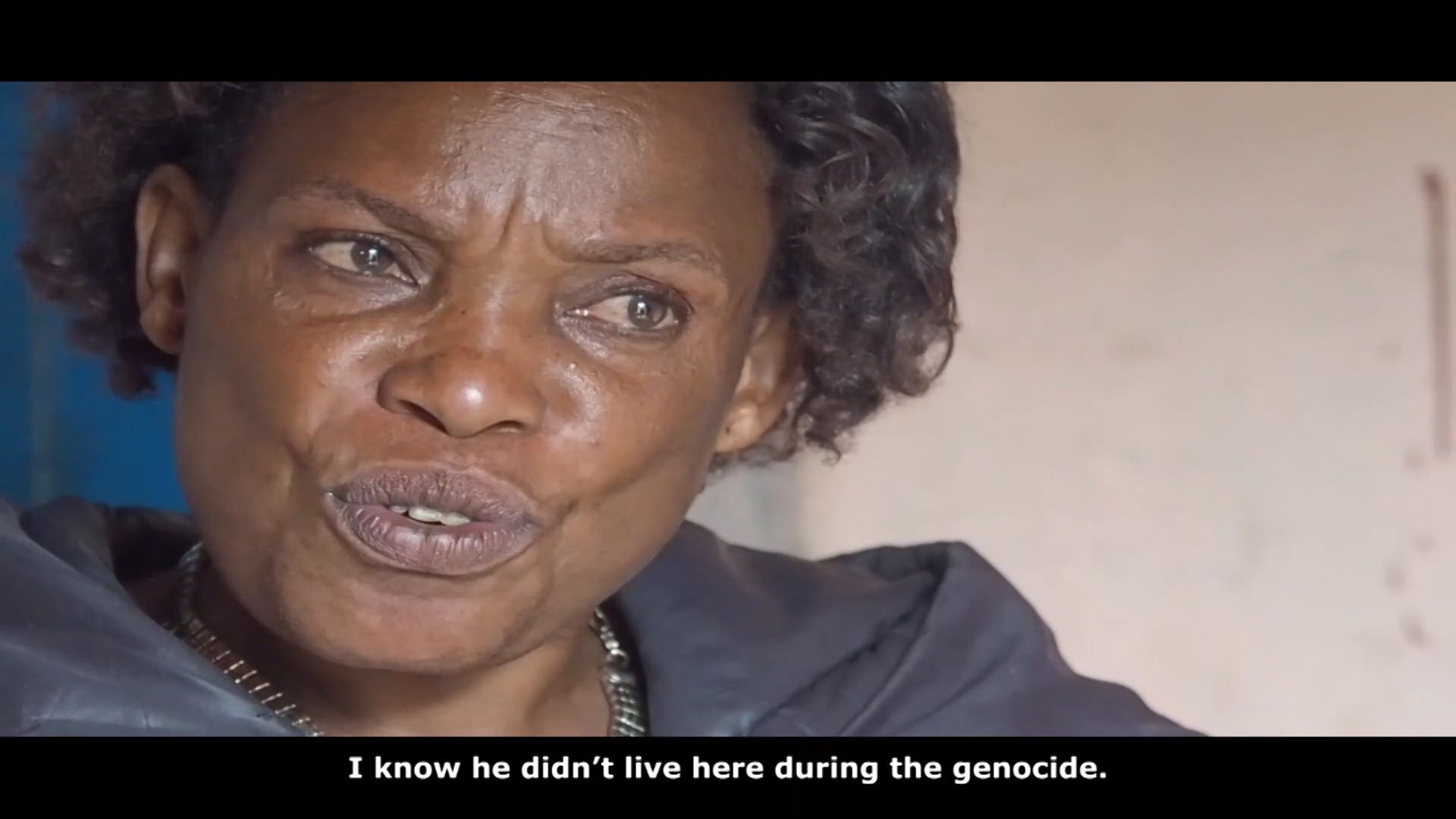

Curiously, Hylleberg and Mugisha accompanied the Danish crew in Busasamana village to investigate Twagirayezu`s alleged crimes, and several interviews by the DRTV crew were conducted in their presence.

They listened in on prosecution witnesses who were undoubtedly providing evidence against Twagirayezu. The journalists didn’t find it unprofessional that they would visit witnesses along with the son of the suspect!

Naturally, their reports were sloppy. In one instance they claimed that five of the six key witnesses had deviated from the testimonies they had initially given to the Danish police. However, the journalists did not reveal to their audience that the testimonies of several other witnesses they had interviewed, people who were present and had seen Twagirayezu at the crime scene, had remained consistent with the claims they had made to the Danish police.

In other words, it seems that the journalists had come to Rwanda to push Hylleberg’s and Mugisha’s agenda.

Moreover, the journalists made up quotes that did not represent what the witnesses had told them and only one, not five as they claimed, witness, Pastor Théophile Kaberuka, had changed his testimony on the account that he had confused the identity of the suspect with someone else.

If anyone had been inconsistent among the witnesses they encountered, it was on the side of the defense where those interviewed could not recall the dates of their interactions with Twagirayezu. Moreover, when asked about the petition of his presumed innocence they signed, their answer was: “We knew nothing about the content of the petition, we all just signed because our Pastor had asked us to in order to give a chance to our friend Twagirayezu to get released.”

Images of how all these testimonies as they unfolded in court were recorded by Thomas Overgaard Nielsen, the camera operator; however, these testimonies cannot be found anywhere in the broadcasted documentary.

Manipulation of witnesses

During Gacaca trials, it was discovered that suspects would cooperate with witnesses, and other suspects, and refuse to testify. Known as “CECEKA” or “keep quiet”, it was an elaborate system of a cover-up meant to circumvent justice in the proceedings.

Upon the departure of the Danish journalists, we conducted our own investigations on the case and found out that; Léoncie Ukwitegetse, a sister to Twagirayezu, who lives in Busasamana, attempted the ceceka approach threatening witnesses from testifying against her brother.

Other witnesses were bribed with foodstuffs and told that it had been Twagirayezu who had provided it and were in return asked not to testify against him; others were promised money if they could recant their testimonies but they refused to take the bribe.

Twagirayezu, his sister, and the entourage tried to conceal this corruption under the guise of giving aid to their neighbors. Crucially, the journalist of the DRTV overlooked all these incidents of witness tampering in the documentary they broadcasted.

Instead, they decided to advance the narrative that it is not possible to have a fair trial in Rwanda, one that got the backing of Jan Pronk, the former Dutch Development Minister.

A fair trial in Rwanda

Any credible justice system on civil and common law adheres to norms of a fair trial, the presumption of innocence, the right to equal justice, and the right to legal representation, among other rights of the defendant, including ensuring human conditions of detention and refraining from torture.

Further, governments that have extradited Genocide fugitives from Europe and the U.S. have ascertained that indeed Rwanda respects these human rights norms.

Indeed, since Twagirayezu’s arrest and trial all the above elements have been respected, even as Hylleberg and Mugisha persisted in making false claims that he would not get a fair trial in Rwanda.

It is not surprising that experts with knowledge of Rwanda’s judicial system disagree with them. Professor Phil Clark, who specializes in transitional justice, describes Rwanda’s judicial system in these terms:

“Rwanda’s judiciary has created specialized processes to deal with extraditions and transfers of Genocide suspects. It has been a high priority for Rwanda, and this has resulted in a robust system. The country’s best judges and lawyers and resources are dedicated to dealing with these cases,” Professor Clark said, adding, “I would argue that these are cases that Rwanda does best.”

Professor Clark refers to the acquittal rate of 30% in Gacaca courts and 25% in formal courts as proof of fair trial, “This is not something that we thought possible…It is not a system that is meant to find genocide suspects guilty, but rather increasingly delivering fair trials,” Clark has observed.

Serge Brammertz, the Prosecutor General of the International Residual Mechanism for Criminal Tribunals (IRMCT) shares the same view:

“In the late 90s and early 2000s, there were initially hesitations of transferring Genocide cases to Kigali… but those hesitations have been scrapped for more than ten years ago” Brammertz has noted, adding that since then different cases were transferred by the ICTR to Kigali. “We designated a team on following and evaluating the trials and their reports came out positively, confirming that defense rights were respected,” Brammertz observes.

Brammertz has also dismissed reservations against the credibility of Rwanda’s courts as being politically motivated. “This is something we have witnessed with several other cases, for example with the ongoing trial of Kabuga. But most of these critics are political, aimed at discrediting the judicial system in place” he said.

To date, Rwanda has issued over 1,000 arrest warrants for Genocide fugitives. Half of these individuals are in African countries; the other half are in European countries where they have found a safe haven, with the countries refusing to either try or extradite them to face justice in Rwanda.

“Thousands of victims are still waiting for justice to be served… Inaction is unacceptable,” a frustrated Brammertz has said.

This impunity is possible due to the protection that genocide suspects receive from politicians like Hylleberg. It is a pain that genocide survivors have had to endure for 29 years and counting.

By Adeline Umutoni, Marc Hoogsteyns